Unfinished – C.R.A.C.

Roman Center of Contemporary Art

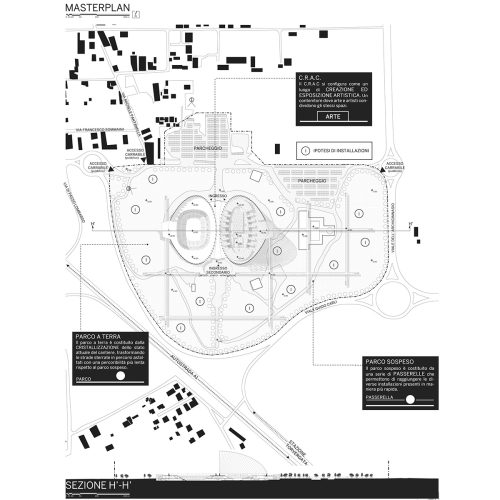

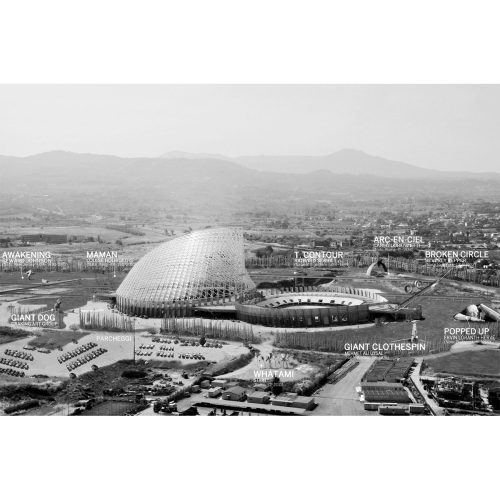

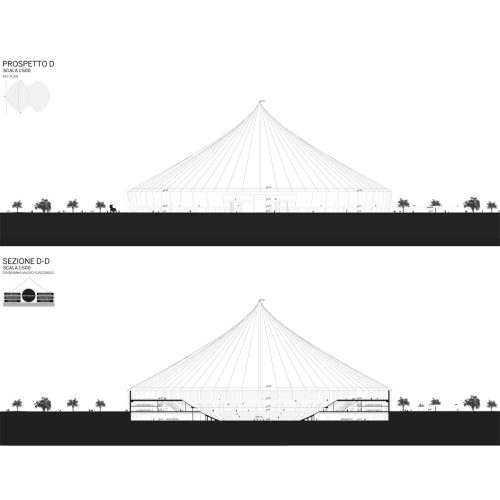

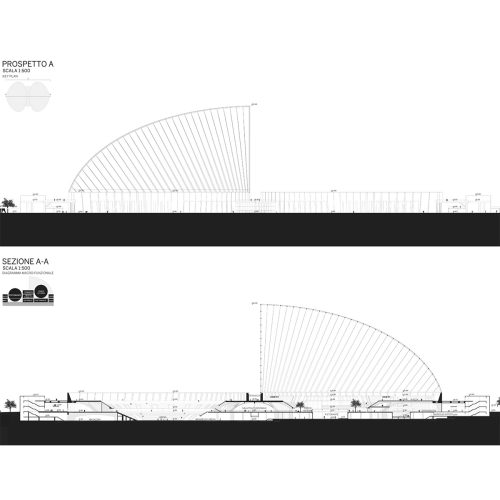

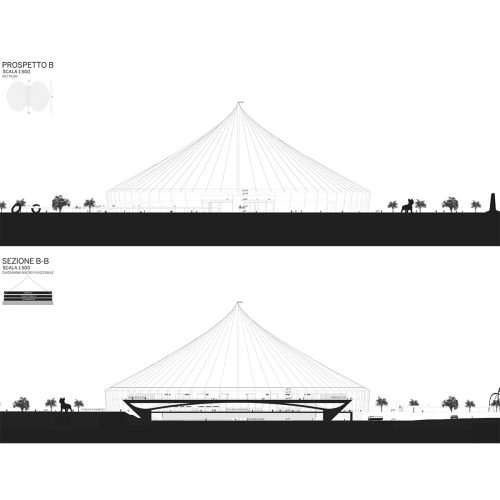

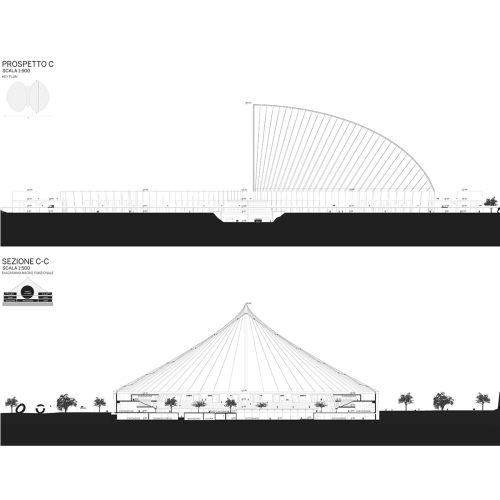

The project idea is based on the “crystallization” of the Tor Vergata Sports City, meaning its activation by simply introducing new functions without excessively altering its incomplete state. The Sports City will thus be transformed into the Roman Contemporary Art Center (C.R.A.C.), introducing new functions related to the artistic sphere (visual and performing arts), creating a new space for the production and exhibition of contemporary art. The external park will become a true extension of the C.R.A.C., also becoming a place for artistic exhibition and creation.

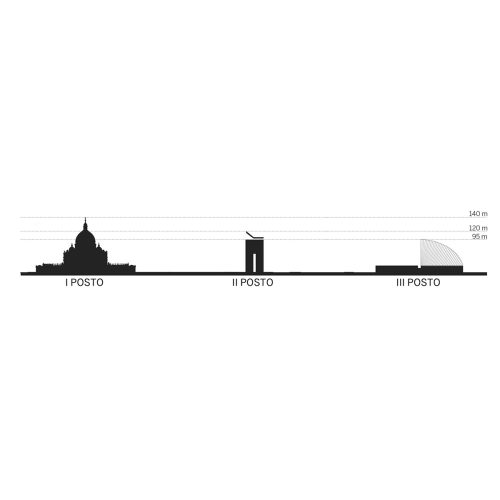

The crystallization process, aided by the spatial configuration and the approximately 90-meter-high metal structure that defines the Sports City as a true landmark in the city of Rome, aims to establish the structure as a symbol of incompleteness, serving as a warning against poor design and future planning.

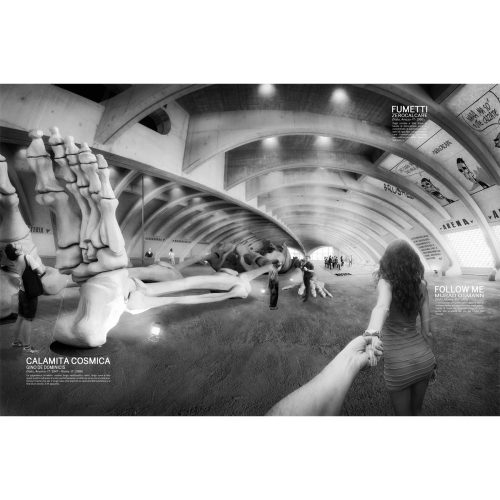

The choice of art as the main theme for the project stems from the desire to explore the relationship between an unfinished, incomplete space and art itself. A space that transcends the concept of the “white box” – a sterile museum where art is highlighted by the total homogeneity of the space. Hence, the intention to also study the relationship between art and social life, which has always played a significant role in all societies that have reached a certain level of development. G. Plechanov wrote that: “It is not society that is made for the artist, but the artist for society.” Therefore, art has always contributed to the improvement of society’s organization, even though the role of art has often been marginalized within it. In the “Manifesto of the Third Landscape,” Clément theorizes that abandoned spaces attract species not accepted elsewhere. This is certainly true in modern society as well, where abandoned places are often inhabited by those “rejected” by society. Thus, the project idea is oriented towards designing a space capable of hosting an artistic community in an environment with strong characteristics of abandonment, like the Sports City.

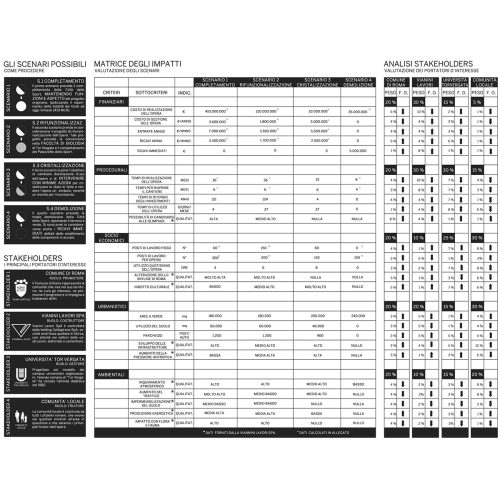

The desire to define an appropriate intervention for unfinished works led the research into a dimension composed of several possible intervention scenarios. The choice of the best scenario for Santiago Calatrava’s Sports City was developed using a multi-criteria socio-economic analysis technique, aimed at selecting the most satisfying option in relation to the objectives, in a transparent and scientific way. This multi-criteria analysis consists of a wide range of techniques capable of relating the qualitative and quantitative aspects of a scenario.

The multi-criteria techniques are divided into two distinct phases:

– The first phase, where all the data and key elements of the project are collected and organized.

– The second phase, where this data is aggregated.

While the procedure for the first phase is common to all multi-criteria techniques, the second phase varies depending on the scenarios and techniques used. In fact, the data can be aggregated either completely or partially. In the first case, the simpler one, the decision-maker is always able to express a preference. In the second case, there is no predefined scheme for the decision-maker’s preference.

Specifically, for the thesis, the first phase defined four hypothetical scenarios: completing the project, repurposing it with the proposed conversion of the Sports City into a greenhouse, crystallization, which aims at changing the intended use with minimal interventions, thus preserving the current state, and finally, demolition. Once the scenarios were defined, the macro evaluation criteria were identified: financial, procedural, socio-economic, environmental, and urban planning, which were further divided into five more detailed sub-criteria. The next step was to identify the main stakeholders: the City of Rome, Viannini Lavori, the University of Tor Vergata, and the local community, along with the importance (weights) each of them had regarding the different criteria considered.

In the second phase, the data was processed using the Weighted Sum Model (WSM). This method, also used by legislators to define the most economically advantageous offer, consists of defining a valuation matrix that allows identifying the best solution by crossing the list of weighted criteria, in relation to their respective importance, with each stakeholder. This is done through mathematical weighting of the data, after a normalization process to make them comparable. This system produced a ranking in which the scenarios are positioned according to the benefit for each stakeholder.

The result of this study was surprising. For each stakeholder, the best intervention was found to be crystallization: inaugurating the building by simply introducing new functions with minimal adjustment interventions, without excessively altering its formal characteristics.

Sara Marini, analyzing A. Corboz’s text, defines the palimpsest as “the insertion into a given space, already occupied by a text, of a new writing, the project as the insertion of an anomalous object that dictates new rules in a given space.” An action that does not produce waste, working on emphasizing the existing and changing the rules.

The project undertaken, therefore, seeks to crystallize the status quo of Calatrava’s work while at the same time defining a new configuration through a palimpsest capable of redefining Calatrava’s project. To this end, three operations were planned: the application of new prefabricated elements that are distinguishable from the pre-existing structure, spatial repurposing, and the consequent reconfiguration of flows. These operations aim to respect the principle of minimal intervention, in order to ensure the concept of crystallization.

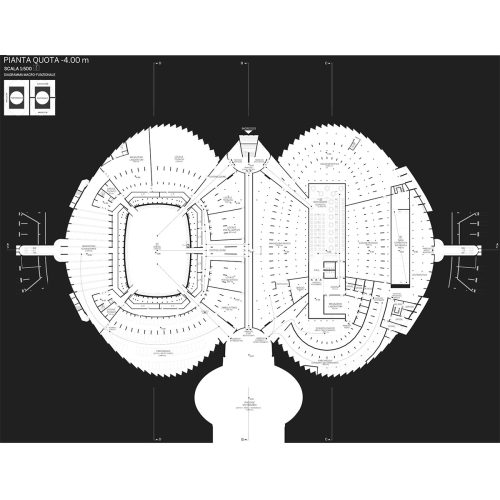

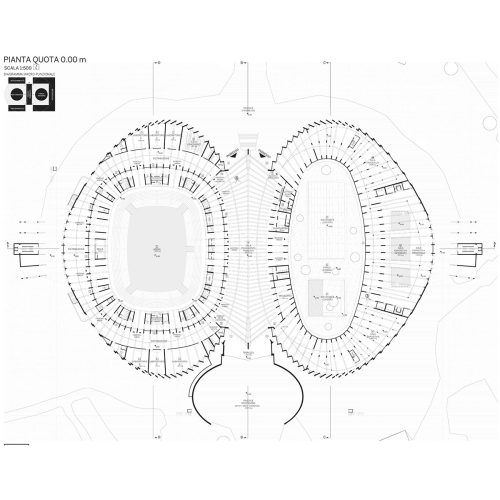

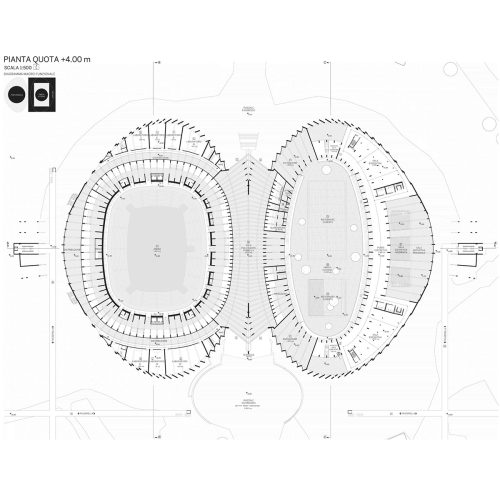

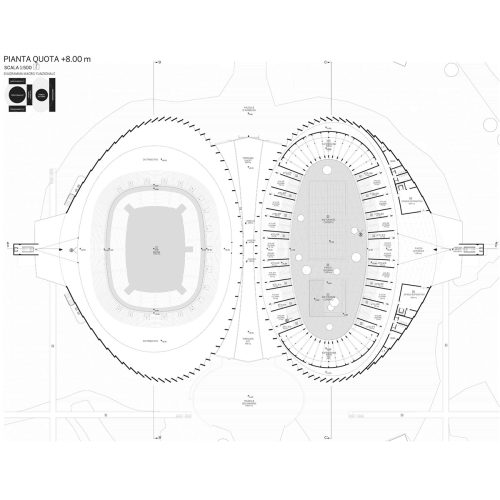

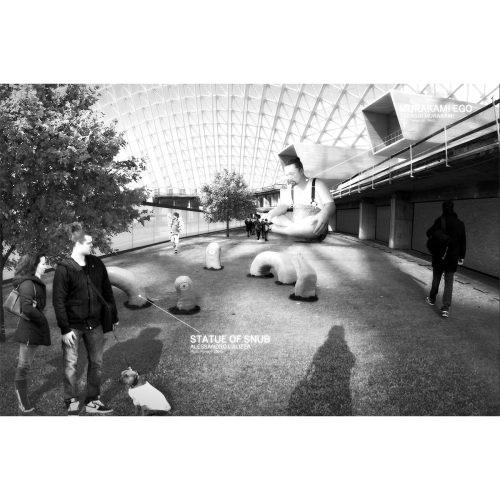

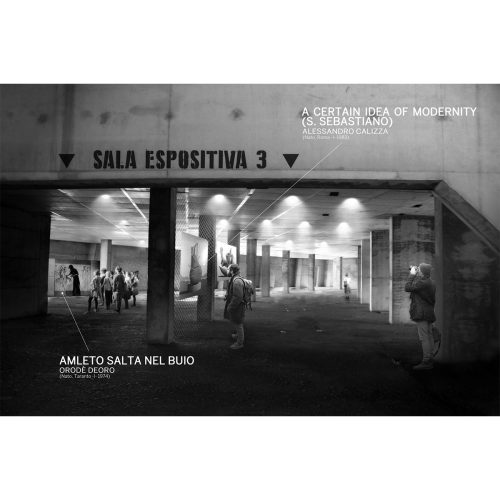

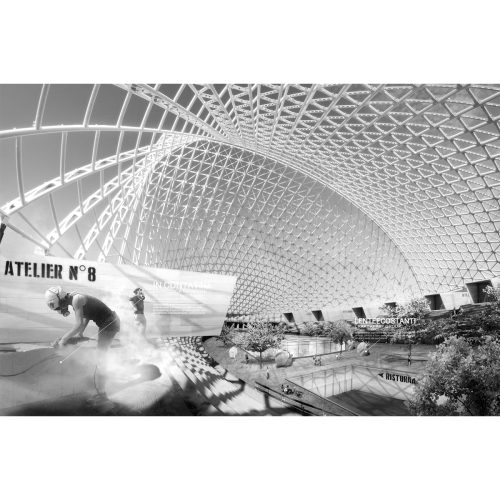

The first operation carried out involved the repurposing of the spaces within the Sports City. These spaces, left incomplete according to the original project, were redefined based on the idea of transforming Calatrava’s design into the Roman Center for Contemporary Art. Therefore, the question of how to intervene to give meaning to these unfinished spaces was answered with a simple operation of repurposing the environments solely through their formal and spatial quality. For example, the large entrance foyer, while maintaining its public space features, is transformed into a multipurpose hall capable of hosting a wide variety of cultural events.

The second operation involved dividing the previously repurposed space using different types of partitions, in order to redistribute the original flows of the Sports City project. The resulting new spatial configuration thus determines a new usability of the space, functional to the new activities introduced by the project. These partitions come in three different types. The first, transparent, was applied to access points and areas where natural light was needed. The second, semi-opaque, made of a wide-mesh metal grid, maintains the spatial relationship between environments while organizing and directing the movements of the CRAC’s visitors. Lastly, the opaque partition, made of OSB panels, was used not only to reconfigure flows but also to change the spatial perception of the environments.

Finally, always following the principle of minimal intervention, a few new architectural elements were added to the pre-existing structure. These elements are grafted onto the already-built structures, standing out as easily distinguishable components. All of these are prefabricated and were added where the existing structure could not be adapted to the new functions required by the CRAC. For example, the ateliers are the main architectural elements introduced by the project. They are arranged around the perimeter of the internal park and overhang the areas that were intended to be the stands of the swimming stadium.

NOTE:

1 – G.V. PLECHANOV, L’arte e la vita sociale, Mosca 1912.

2 – G. CLÉMENT, Manifesto del Terzo paesaggio, Macerata 2005.

3 – F. BATTISTI, Valutazioni comparative per lo sviluppo dei processi di riqualificazione del territorio a partenariato pubblico-privato: una proposta di metodo, Dottorato di Ricerca in Riqualificazione e Recupero Insediativo, Roma 2012.

4 – S.MARINI, Nuove terre. Architettura e paesaggi dello scarto, Macerata 2010.

Marco Tanzilli

BIBLIOGRAFIA

C. BRANDI, Teoria del restauro, Einaudi, Torino 1963.

J.G. BALLARD, La civiltà del vento, Mondadori, Milano 1977.

G. SIMMEL, Die Ruine, Klinkhardt, Leipzig 1911, traduzione di G. Carchia in Rivista di Estetica, 8, 1981.

J. RUSKIN, Le sette lampade dell’architettura, Jaca Book, Milano 1982.

M. AUGÈ, Nonluoghi. Introduzione a una antropologia della surmodernità, Elèuthera, Milano 1993.

B. TSCHUMI, Architecture and Disjunction, The MIT Press, Cambridge 1994.

F.PURINI, Comporre l’architettura, Universale laterza, Bari 2000.

M. DORING, “La nascita della rovina artificiale nel Rinascimento Italiano ovvero il Tempio in rovina di Bramante a Genazzano”, in Donato Bramante: Ricerche, proposte, riletture, a cura di F. P. Di Teodoro, Urbino 2001.

M. AUGÈ, Rovine e macerie. Il senso del tempo, Bollati Borringhieri, Parigi 2004.

R. KOOLHAAS, Junkspace, Quodlibet, Macerata 2005.

G. CLÉMENT, Manifesto del Terzo paesaggio, Quodlibet, Macerata 2005.

S. ZALMAN, The Nun-u-ment. Gordon Matta Clark and the contingency of space, New York 2005.

F. Cellini, “Il rudere”, in Il rudere tra conservazione e reintegrazione. Atti del convegno internazionale (Sassari, 26-27 set 2003), a cura di B. Billeci, S. Gizzi, Gangemi editore, Roma 2006.

A. BRUNO, “I ruderi di nuova generazione”in Il rudere tra conservazione e reintegrazione. Atti del convegno internazionale (Sassari, 26-27 set 2003), a cura di B. Billeci, S. Gizzi, D. Scudino, Gangemi editore, Roma 2006.

J.G. BALLARD, L’isola di cemento, Feltrinelli, Roma 2007.

F. PURINI, Attualità di Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Libria, Melfi 2008.

T. MATTEINI, Paesaggi del tempo. Documenti archeologici e rovine artificiali nel disegno di giardini e paesaggi, Allinea, Roma 2009.

G.MENZIETTI, Rovine contemporanee. Resti dell’architettura Italiana tra gli anni ‘60 e gli anni ’80, Dottorato di Ricerca Internazionale Villard d’Honnecourt, Madrid 2009.

A. UGOLINI, Ricomporre la rovina, Alinea editrice, Perugia 2010.

S. MARINI, Nuove terre. Architettura e paesaggi dello scarto, Quodlibet studio, Macerata 2010.

F. BATTISTI, Valutazioni comparative per lo sviluppo dei processi di riqualificazione del territorio a partenariato pubblico-privato: una proposta di metodo, Dottorato di Ricerca in Riqualificazione e Recupero Insediativo, Roma 2012.